Newer West Baton Rouge residents may not know that our parish has its own ghost town. Well, ghost swamp might be more accurate. On wooded land now used primarily by Brusly Hunting Club members once stood the town of Morley which, during its peak, was one of the biggest towns in West Baton Rouge.

“I learned about the town the first time I went to my daddy’s hunting camp in the early 1960s. My father, Will Hebert, a charge of the Brusly Hunting Club, built his little camp on the Parish Canal near Bayou Choctaw. On a hill next to his camp stood one corner of a brick building. My daddy explained that the building had been used by the Morley Cypress Mill, and the slough (“slew”) behind his camp had been used to float timber to the mill. He told me about the town, and later showed me what was left of it in the woods, which included a big brick smokestack and concrete piers where the mill once stood. Old bottles , and glass electrical insulators littered the woods, some of which I collected and still have. I asked my daddy why there was nothing left by woods. “Mother Nature always reclaims her own,” he said. But how could a whole town just disappear? Many years later, I learned some of the factual history.”

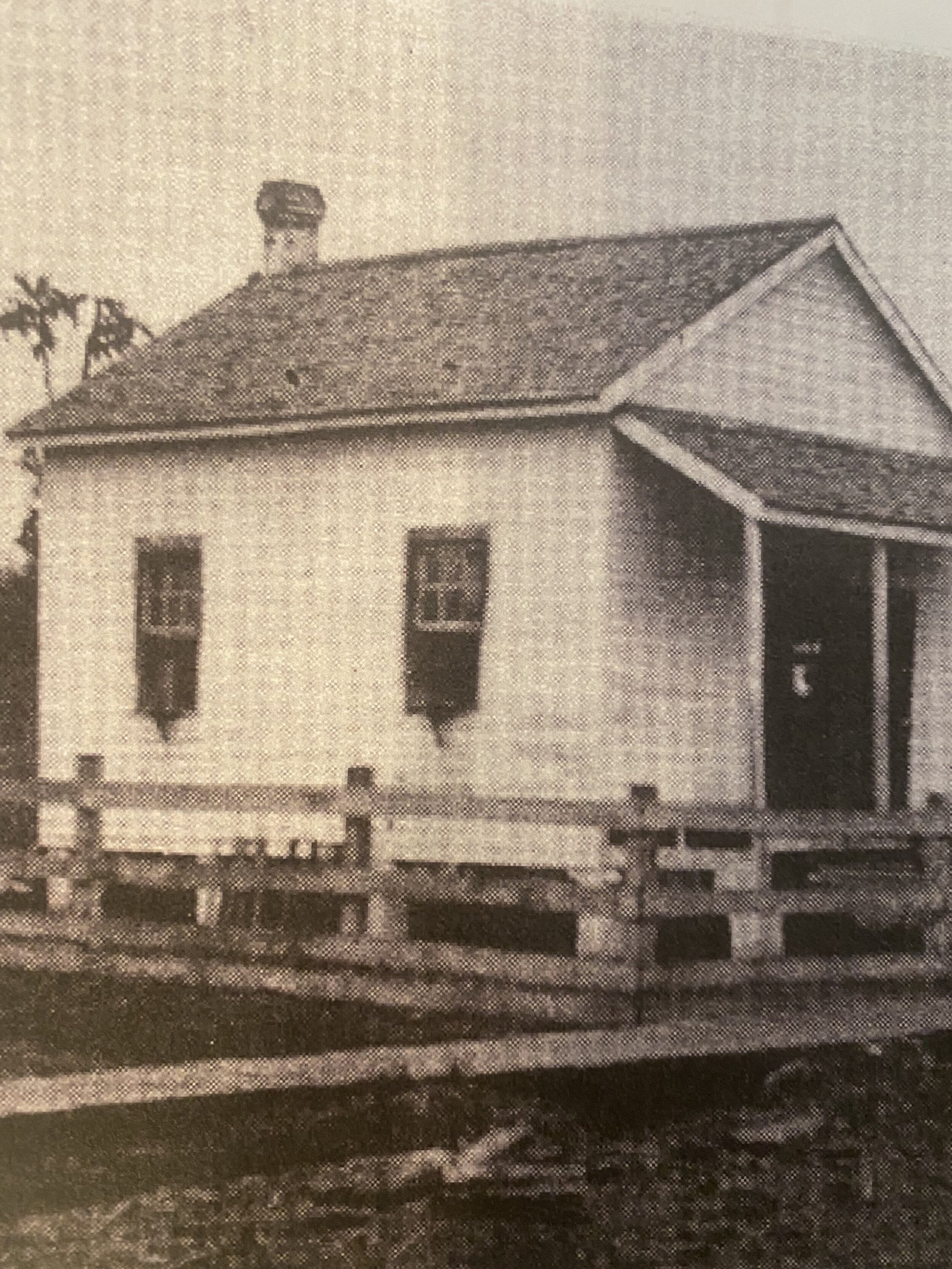

Morley homes and businesses on the south side of the railroad track, circa 1920. The store and post office are in the foreground. photo courtesy of West Baton Rouge Museum

After starting the mill, H.T. Morley built housing for mill workers and their families, along with businesses and other establishments to fulfill their everyday needs. Most of the structures were built from local cypress, and it wasn’t long before a thriving town developed around the mill. It was said H.T. ran the town that bore his name with the same dogged determination with which he ran the mill.

Located 6 miles west of Brusly and 8 miles northeast of Plaquemine, Morley was situated on either side of the Texas and Pacific railroad tracks. H.T. Morley’s vision grew to a community of over 300 residents by 1910, and the steam-powered cypress mill churned out “cypress lumber, shingles, laths, and pecky posts” according to newspaper ads from the period.

Some employees of the Morley Cypress Mill and Lumber Company were from nearby areas, but moved to Morley for work. Boarding house operator Maggie Wunstel was from Grosse Tete. Sales manager W.J. “Willie” Oubre was from Convent, while yard foreman Joseph Oubre, and mill mechanic Florian Michel were from Donaldsonville. My grandfather, Achille Altazan moved from Plaquemine to work as a clerk in the store. My mother’s three oldest siblings – Helen, Louis, and Eric Altazan – were born in Morley. Other “local” townspeople included the Landrys, the Brauds, and the Lefebvres.

Several workers came to work at the mill from Brusly, like night watchman Walter Landry. In the photo to the right, second from left is Eugene Gros, grandfather of Brusly resident Judy Thousand. Standing directly to the right side of the sign is Omer LaBauve, Sr., my great-uncle, and grandfather of Brusly resident Matt LaBauve.

In addition to the mill, the town would eventually include 132 homes, a large store and post office, a dance hall and motion picture theater, an ice house, a butcher shop, a Baptist church, a doctor’s office, a schoolhouse, a saloon, a boarding house, a jail, dairy service, and a train depot. Mr. Morley’s big house was the only one east of “Little Bayou.” His brother, L.M., a bachelor, lived in town with an aunt, Miss Eldora Payne.

The 107 homes provided for African-American workers were located on the north side of the T&P railroad tracks, along with the mill and saloon. Supervisor’s homes and other businesses were located on the south side of the tracks. Some of the homes featured white-washed picket or rail fences.

There weren’t many roads in the wilderness, but few residents – other than H.T. Morley – had automobiles anyway. The roads that existed were made of cut logs covered by sawdust. The town did, however, have wooden sidewalks for foot traffic. Morley, Louisiana made up of Eighth Ward of West Baton Rouge parish, and was represented by resident police juror Joe Collins. Mr. Collins and the Policy Jury were instrumental in later connecting the sawdust Morley Road with the Choctaw Road leading to Brusly.

Mail was delivered to Morley twice daily by train, and the Post Office was located in the back of the store. In addition to being Secretary of the Morley Lumber Company, L.M. Morley also served as the town’s postmaster.

Before the completion of the road into Morley, residents needing contact with the outside world would catch the train to the “Baton Rouge Junction” (later renamed Addis) or to Plaquemine. W.M. Oubre, who was sales agent and general manager of the mill, was also the ticket agent for the Texas and Pacific Railroad.

In the “Seventeenth Annual Report of the Railroad commission of Louisiana”, published in 1916, order number 1908 concerns a petition by Morley residents requesting that a train passenger station be constructed so riders would not have to wait in the elements, or be forced to board and disembark the train by traversing the steep railroad embankment. By this time, it was estimated that Morley had between 750 and 1,000 inhabitants. Since the map of the town indicates there was a depot, apparently the petitioners were successful in their efforts.

The schoolhouse was a small one-room building, and included students from the first through seventh grade. Students in higher grades would later ride a bus to the school in Brusly.

Since there was no Catholic Church in town, Morley residents attended services at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church in Brusly whenever possible. Citizens who died usually buried in either Brusly or Plaquemine, although when store clerk Frank Mollere died from yellow fever in Morley on November 29, 1912, he was brought home to Port Barrow in St. Landry parish for burial.

Dr. Paul Bernard Landry served as the town’s physician from 1911 to 1915. He attended the sick and needy at his small Morley office two days a week. His son recalled that Dr. Landry would sometimes have to throw tree branches into the low spots of the road to Morley so its high-wheeled Ford Model T could travel into town. After ending his mill employment in 1915, Dr. Landry moved to Port Allen and opened an office near the Port Allen drugstore, which he owned. He sold that business in 1920 to Thomas Cronan.

Minor flooding in the area of Morley was always a possibility, since the town sat between two bayous. In 192, however, a little over two weeks after the sinking of the Titanic, an unforeseen threat came from Point Coupee parish when the Mississippi River washed through the levee at the small town of Torras, LA on May 1st.

The “Torras Crevasse” not only flooded towns in Pointe Coupee, it allowed the river’s muddy waters to rush into areas to the south through the 800-foot breach at 12 miles per hour. Affected areas included West Baton Rouge, Iberville, Assumption, Lafourche, Terrebonne, St. Martin, Iberia, St. Mary and St. Landry parishes.

Homes in Morley’s African-American community sit submerged as a result of the Torras Crevasse, 1912.

photo courtesy of West Baton Rouge Museum

It was estimated that as many as 115,000 people were rendered homeless by the flood. Much of the evacuation of residents and bringing in of supplies were done by trains.

New Orleans newspapers reported some fatalities, and that “thousands more are in imminent danger of death by drowning or starvation and exposure” as a result of the flooding. Morley, like many other areas, was devastated by the flood. Fortunately, the only casualty reported in Morley was that of one of the mill mules.

H.T. Morley was well-known in Baton Rouge business circles, and was an active Knight Templar and Mason, as well as a charter member of the Baton Rouge Country Club. Reportedly, in 1915, Morley had been offered an investment opportunity by a Michigan friend, Henry Ford, who needed capital for his fledgling car company. Morley turned down the offer, but apparently Ford didn’t hold a grudge, as it was rumored that the Ford Model-A automobile H.T. later drove through the swampy areas of his property was sent by barge as a gift from old Henry himself. While there may not be documented proof of these stories, it is known that Morley’s son-in-law, Charles Morgan, later worked for the Ford Motor Company. Also, many years later, Morley’s grandson, Morley Morgana, would become good friends with Fords grandson, Henry Ford II.

Morley may have used the Model-A in the backwoods, but he also owned a much sleeker Stutz Bearcat for city travel. On May 22, 1923, Morley was returning from lunch at the Country Club in Baton Rouge with his uncle-in-law, 77-year-old George Coswell, and four ladies. On that wet afternoon, as Morley and his passengers traveled south on the River Road just below the Port Allen ferry landing, a Nash automobile attempted to pass Morley’s Bearcat. In an attempt to stay in front of the Nash, Morley gunned his powerful engine, but the car’s wheels skidded in the wet gravel, and he lost control and swerved into the ditch. George Coswell was killed instantly, and H.T. Morley, fatally injured, died at the ferry landing enroute to St Mary’s Sanitarium on Main Street in Baton Rouge with Dr. Landry at his side. All four ladies – Mr. Coswell’s daughter, Emma Dusenbury; Mr. Morley’s aunt, Eldora Payne; Mrs. Dan Utley and Mrs. Reginald Duval – survived.

As the town disappeared, bits and pieces were resurrected in new locations. Billy Hebert’s grandfather, Robert Hebert’s house next to the tracks at the corner of West Main Street and Highway 1 in Brusly was originally located in Morley. According to Theresa LeJeune Alexander, her father, Sidney LeJeune, purchased the house, dismantled it in Morley, and then paid someone $100 to rebuild it at its present location, exactly as it had been at its original site in Morley. Several other homes in Brusly were reportedly also moved from Morley. Joseph J. Templet of Plaquemine purchased and dismantled the mill building and other structures, and shipped them by barge to his property in Indian Bayou, where the materials were used to build several homes.

Today, you won’t find Morley, Louisiana on any map, although the railroad bridge that spans the Intracoastal Waterway near where the town existed is officially known as the “Morley Bridge” and hunters who frequent the woods where the mill and town once stood still refer to the area as “Morley Swamp.” The last Morley family members who knew the town, however, are gone – Abigail Morley Morgana died in Grosse Point, Michigan in 1972. Her son, Morley Morgana, died in Baton Rouge in 2007.

What’s left of a once busy, thriving, and vital mill and town are scattered piles of brick, concrete, and steel remnants, grown over with twisted vines and dense underbrush. Woods populated by squirrels, rabbits, deer and other creatures belie the fact that the area was once populated by hundreds of humans. Cypress trees have returned to the area, and the slime-covered sloughs are stagnant and still. All silently witness to what my daddy proclaimed all those years ago – Mother Nature has reclaimed her own.

So, when it’s all said and done, why should we care about a place that’s been gone 90 years? Well, while tiny Morley, Louisiana may not have the historical significance of other “ghost towns,’ it was once part of our parish, and the mill provided jobs for ancestors of families still in the area. Our people lived, worked and died there. Even though no part of the town exists today, its impact on the residents of West Baton Rouge parish is still noteworthy and its memory deserving of preservation.